Reach for the moon. If you fall short at least you’ll be among the stars.

High expectations are the key to everything. – Sam Walton

Persistent people begin their success where others end in failure. – Edward Eggleston

It’s amazing what ordinary people can do if they set out with preconceived notions. – Charles F. Kettering

Without continual growth and progress, such words as improvement, achievement, and success have no meaning. – Benjamin Franklin

To accomplish great things, we must not only act, but also dream, not only plan, but also believe. – Anatole France

Excellence is not being the best; it is doing your best.

Sent from my Verizon Wireless 4G LTE smartphone

At a crucial moment with the best possibility of an ESEA re-authorization on the near horizon and with only about one year left before the end of the Obama administration, long-serving Education Secretary Arne Duncan has stepped down. It is unclear why, but we do know that the President wanted Duncan to finish the course: “I’ll be honest. I pushed Arne to stay,” he said at a televised news conference at the White House Oct. 2. “He’s one of the longest-serving education secretaries in history and one of the more consequential.”

Duncan has certainly been a polarizing figure in education politics and reform over the last 7 years for two main reasons. First, the Education Department was granted a unique opportunity to implement its policies under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. This program involved $100 billion for education, which the Administration used to encourage teacher evaluation based on student achievement, college and career ready standards, and most notably Race to the Top, a grant program for school turnaround. Conservatives, although initially supportive, also grew disenchanted with Duncan’s support for Common Core.

Second, because of the inability of Congress to push through a new re-authorization of the ESEA, of which No Child Left Behind is the most recent iteration, the Education Department was left in a situation in which it became the de-facto legislator of education policy. Because the punishments associated with NCLB were starting to come to fruition 10 years after it was passed in 2001-2002 and no states had lived up to the strict standards imposed by the law, the Education Department under Duncan instituted a system of waivers that granted states clemency in return for promises of following education policies favored by the Obama Administration. This is the situation that began to rankle many of the left-leaning education professionals who had initially supported Duncan’s efforts.

Looking back at Duncan’s career as Education Secretary provides a perfect window into U.S. Education policy reform struggles in recent years. Because Duncan has pursued policies across the political spectrum, he has received praise and condemnation from those on both sides of the aisle. And it is in part for this reason, why it is still an open question whether a new education bill will be passed and how much that bill might sweep back some of the changes made by Duncan which granted the Education Department unprecedented powers in American education. It will now be the job of the new Education Secretary, John B. King Jr. (the acting deputy secretary of Education with a background in New York State education administration), to navigate the education waters for the remainder of the Obama Administration.

Ray Nunziata

Ray

President,

Gas Jockeys Inc

CELL: 813.205.4442

Small Loans, Big Problem

September 28, 2015

By

Community colleges are relatively affordable, and their students tend to borrow less than those who attend other types of institutions. Yet the debt students rack up at community colleges is troubling.

The reason is that students who attend two-year colleges struggle to repay even small loans, and often default on them, a concern that is reinforced by a new study from one of the sector’s primary trade groups — the Association of Community College Trustees.

Just 17 percent of community college students take out federal loans, the report said, which is much less than at four-year public institutions (48 percent), private colleges (60 percent) and for-profits (71 percent). But students who attend community colleges are more likely to default.

The national default rate for community college students three years after they enter repayment is 20.6 percent, the report said, compared to the overall average of 13.7 percent.

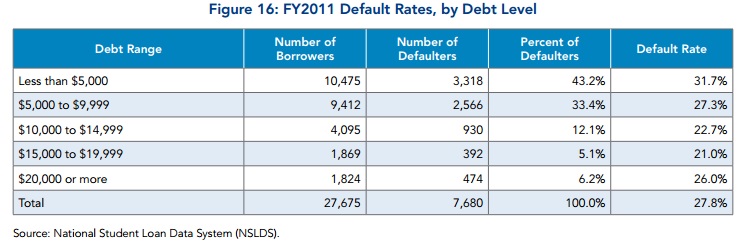

The association looked at how students are faring at Iowa’s 16 community colleges, and the picture isn’t pretty. Of the 27,675 Iowa community college students who entered repayment 4.5 years ago, 7,680 — or 27.8 percent — defaulted on their federal loans by January 2015.

The state’s community colleges are relatively expensive — annual tuition and fees are an average of $4,541 in Iowa, compared to the sector’s national average of $3,347. Borrowers in the sample took out an average of $8,287 in loans.

While the report is based on federal data, it pulled information that only is available to researchers at the U.S. Department of Education, colleges and federal lenders. The 16 Iowa colleges requested and shared the data. Using it to write the report were two researchers — Colleen Campbell, senior policy analyst at the association, and Nicholas Hillman, assistant professor of educational leadership and policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

They identified four key findings, which might be surprising to some:

(1) Students who borrow the least are the most likely to default.

A growing body of research has found that student loan defaults are concentrated among the millions of students who never earned a degree. Graduates who borrow the most tend to earn the most. But those who take on even a small amount of debt with nothing to show for it face a relatively high risk of defaulting.

This report bolsters that finding. Nearly half of the defaulters in the Iowa sample borrowed less than $5,000. Most borrowed less than $10,000. But the default rate for students who took out less than $5,000 in loans was nearly 32 percent. And it was 27 percent for students who took out $5,000 to $9,999 in loans.

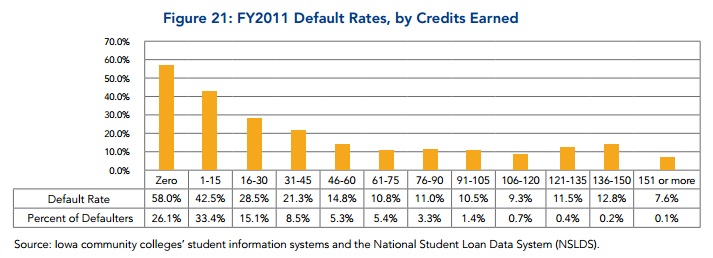

(2) Most defaulters fail to earn a degree or complete many college credits.

Almost 90 percent of students who defaulted left college with debt but no degree or certificate, according to the report. And roughly 60 percent of the defaulters were students who earned fewer than 15 college credits. About 26 percent of defaulters earned no credits at all — the zero-credit-holder group had a default rate of 58 percent. Students who earned up to 15 credits had a default rate of 43 percent.

In comparison, the report found that students who earned the most credits defaulted at the lowest rates. The default rate for students who earned 61 to 75 college credits — enough for an associate degree — was roughly 11 percent.

The report said fixing this problem won’t be easy, because community colleges have open-door admissions policies. Yet it called for policy solutions that promote “academic preparedness and progression,” while curbing borrowing by students in the earliest stages of enrollment. Also necessary are campuswide, data-driven interventions to help student stay enrolled and complete, according to the report.

(3) Many defaulters take no action on their debt.

Among borrowers who went into default, the report said nearly 60 percent did not use loan forbearance or deferment options. But while many did not postpone their payments, even more failed to make a single payment — fully two-thirds of defaulters made no payments on their loans.

Most students’ defaults occurred in the first year of repayment, the report found, and few borrowers dealt with their defaulted debt in the following 3.5 years.

The report cites research finding that students often underestimate how much they borrow, which could influence the large numbers who took no action on their debt. It is also possible that students did not know the terms of their debt, according to the report, and believed they had more flexible repayment options or did not have to repay their loans if they failed to graduate.

(4) Colleges lack complete information on federal loan data.

The National Student Loan Data System contains information on all federal student loans and most federal grants. While it gives financial aid administrators lots of helpful information, the report said the federal system allows little flexibility for data retrieval. Its student record pages are hard to interpret and include no information on loan servicer behavior.

As a result, counseling students and managing a loan portfolio is difficult for community colleges, the report said. And the lack of data on servicers makes appeals, challenges and “data-informed accountability almost impossible.”

Whether you think you can or think you can’t, you’re right.

-Henry Ford